- Episode.8 「世界で評価される馬革専業タンナー『新喜皮革』」

- Episode.7 「ロマンと科学で紡ぐ”XX”の遺伝子 Vol.4」

- Episode.6 「ロマンと科学で紡ぐ”XX”の遺伝子 Vol.3」

- Episode. 5: The DNA of “XX,” Interwoven with a Spirit of Adventure and Science – Vol. 2

- Episode.5 「ロマンと科学で紡ぐ"XX"の遺伝子 Vol.2」

- Episode.4 Starting “XX” Reproducing Project. Vol.1

- Episode.4 「ロマンと科学で紡ぐ"XX"の遺伝子 Vol.1」

- Episode. 3 Vintage Wool Blanket Making Revives in Modern Times Vol. 3

- Episode.3 「現代に蘇るヴィンテージウール Vol.3」

- Episode.2 Vintage Wool Blanket Making Revives in Modern Times Vol. 2

- Episode.2 「現代に蘇るヴィンテージウール Vol.2」

- Episode.1 Vintage Wool Blanket Making Revives in Modern Times Vol. 1

- Episode.1 「現代に蘇るヴィンテージウール Vol.1」

Episode.2 Vintage Wool Blanket Making Revives in Modern Times Vol. 2

Kodawari, roughly meaning persistence in Japanese, is hard to define; its meaning will shift depending on the context. How vintage products are reproduced is a good way to explain Kodawari.

Goto, the CEO of JELADO, a clothing company inspired by vintage American production, says, “We don’t reproduce masterpieces. We reproduce the excitement experiencing vintage products for the first time.”

Human spirit devises a plan and the plan becomes a thing. That product then shows itself in the city with human spirit. When products are guided by the human spirit their foundation is pure Atarimae, - it’s natural. It’s essential to document the pride in the work of the many Japanese professionals, Shokunins, craftsmen, who create this type of products.

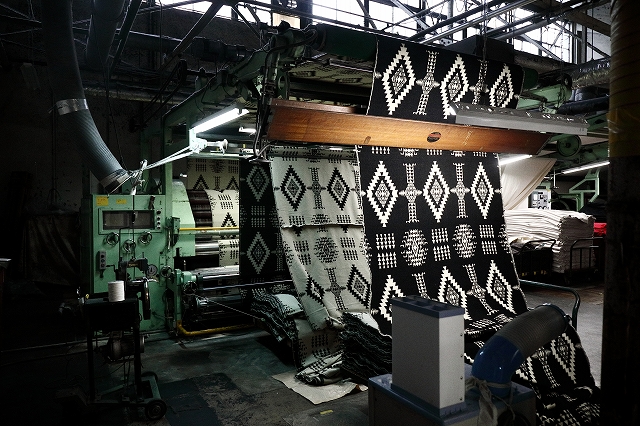

In Volume 1 we discussed the third step, the Seishoku process -how yarns become fabric. Now we are going to report on Seiri Kakou -the finishing process: how the woven blanket fabric is cleaned and turned into a deliverable product.

Let’s head to the Soto Company, which is renown for this kind of finishing process. Soto blends the traditional techniques of Bishu, Japan with the world’s latest digital fabric techniques. We’ll see how the craftsmanship, and pride in a process which originated in 1923, harmonizes with present day JELADO’s vision and creates an unparalleled new product.

Step.4 Rope Senju (fiber refinement)

After Seishoku process has been finished, the blanket undergoes Rope Senju -fiber refinement. Because the just woven blanket is firm and there is machine oil and dirt adhering to it, it needs to be washed and massaged to remove stiffness. Ordinarily, the main purpose of this process is removing unwanted substances, but this factory is unique in that it also prepares to remove the stiffness of the fabric at the same time.

“Only humans can put added value to products.”

A shokunin feels that even if a process is done by a machine, human guidance is critical. “For example, if we remove too much of the wool oil from the fabric, that would damage the fabric texture. Even when we use a fabric we’ve used before, despite it being exactly the same fabric, the machine movements and frequency of washing water exchanged are different every time. We need to understand these conditions and finesse the machine to make the fabric perfect each time. Producing the best possible product drives us”. They’ve been doing Seiri Kakou in Bishu for 100 years. Walking into the factory, the pride and tradition is immediately felt.

Step. 5 Spin-drying and Drying

After the washing process, the blanket gets spin-dried and sent to a drying process. The blanket is set in a machine called a tentering -a structure on which milled cloth is stretched for drying without shrinkage. It conducts both drying by hot air and stretching the blanket. In this process, their original blended resin liquid is also applied to the fabric to have a texture and resilience. In addition, the size of the finishing process facility is represented by the number of the tentering drying machine.

Step. 6 Kimo(Nap-Raising)

The Kimo (Nap-Raising) process uses a drum roll with sharp needles, to nap-raise on the surface and backside of the fabric. To determine how to nap-raise each fabric and how many times it should be processed, a number of tests are conducted with sample fabrics beforehand. The exact number of times that the process is performed is secret, but I saw the front and back of the blanket go through the machine at least several times.

One surprising thing was that when they nap-raise both sides, they untied the joined part of each Tan (a 25m fabric roll) once and retie the part again to keep each Tan straight. I asked them about why they bother to do extra work, and they gave us a simple answer: “If we only think about efficiency and let the blanket get nap-raised without human input, its finish will not meet our standards.”

“Our sensibilities, which can’t be converted to numbers, operate the machines.”

A shokunin told me: “adjusting the nap-raising machine is an essential part of this process.” Each fabric has a different characteristic. Even characteristics of the same fabric will be change according to amounts and conditions. It seems like there should be a science to the process, but that won’t happen in this industry. The only reliable formula is the 100 years of accumulated knowledge and each shokunin’s personal experience.

One thing that the shokunins said really struck me: “For us, using Japanese-made nap-raising machines made decades ago which require human guidance is easier than using up-to-date Italian-made nap-raising machines which operate just by inputting numbers.” Adjusting the nap-raising depth by intuition and hand creates a texture quality that a machine can’t replicate.

“This is the biggest reason that we can’t automate the process: there are too many kotsu (hunches) which only skilled shokunins have, and these kotsu are needed to guide the machine at every step of the process. We may be able to have certain standards to create a structure for mass production, but our shokunin pride doesn’t allow us to do it…… for us, efficiency is bad! Ha!”

STEP. 7 “Senmo(Wool Shearing)”

After the nap-raising process, the fluff on the surface of the woven fabric is not consistent, so they are cut into a fixed length in the senmo (wool shearing) process. Nap-raising process is often recognized as one of the most important processes for finishing woven wools, but wool shearing is also very important because it affects how the fabric textures, colors and patterns look.

“When we receive a work order, we get the general idea of it, but if quality would be compromised we don’t carry out the order exactly as it is. That’s important.”

One shokunin told me: “The wool shearing is the decisive factor for the consumer once they have the fabric in their hand. Therefore, we have to be very careful to maximize the textures created in the nap-raising process when we conduct this process. The quality of this process is greatly affected by who operates the machine, too. All our work always comes with a work order from fabric directors and it’s important for us to understand what the work order essentially means, not the exact numbers written in the document. Then we can start to operate the machine. By checking the blades of the shearing machine, the woven fabric condition, and discrete differences by lot, we sometimes conduct different processes from the work order. The important thing is the achieving the best results, not blindly following the buyers’ instructions. This is how things should be made.”

STEP.8 “Press”

The last process before fabric is submitted to the cutting and sewing factory is the “Press”. This process smoothes and burnishes the woven wool; the press is put between felt fabrics, and then the surface of the fabric is straitened by high-heat steam and pressure. The blanket which JELADO ordered this time is pressed softly to create the vintage American feeling and durability.

And, on to next episode,

Although when people talk about the importance of weaving when it comes to wool, in fact the finishing process is as important if not more so. Also, when we are thinking about the Shokunin, we tend to imagine the shokunin uses primitive tools to create a product; however, I found that though shokunins may in fact operate somewhat modern large machineries, they retain a primitivism -the “Kodawari” as we say in Japanese. Ultimately, there is a big quality gap standard machine operation and how a Shokunin operates the machines.

Goto says, “the fabric finishing process needs more attention because this process is entrusted to giving a life to the fabric and there must be a logical consistency.” I then realized JELADO is producing their products logically and precisely even more than when the masterpieces were created in the past.

In next and final episode, I’m going to introduce the cutting and sewing process mainly to explain how the blanket is finished as a fabric and transformed into a sellable product.

<Text/Ryo Tagata Photo/Seiji Sawada Translation/Kenny>